We have just received official word from the Ecological Society of America (ESA) that our two 2011 “Photography for Ecologists” workshops have been approved. Our team (myself, Molly Mehling, Nathan Dappen, and Neil Ever Osborne) will be leading the two workshops at the 96th annual ESA meeting in Austin, TX in August. The first workshop, which will run from 8am-5pm on Sunday, August 7th, will be a field-based workshop on how to capture intentional, effective images. The second workshop, which will run from 8-10pm on Monday, August 8th, will focus on using visual media effectively in outreach. We’re really excited to bring these workshops to the ESA audience! Stay tuned for more details; I will share the official workshop URL (and instructions on how to sign up) as soon as that information is available.

We have just received official word from the Ecological Society of America (ESA) that our two 2011 “Photography for Ecologists” workshops have been approved. Our team (myself, Molly Mehling, Nathan Dappen, and Neil Ever Osborne) will be leading the two workshops at the 96th annual ESA meeting in Austin, TX in August. The first workshop, which will run from 8am-5pm on Sunday, August 7th, will be a field-based workshop on how to capture intentional, effective images. The second workshop, which will run from 8-10pm on Monday, August 8th, will focus on using visual media effectively in outreach. We’re really excited to bring these workshops to the ESA audience! Stay tuned for more details; I will share the official workshop URL (and instructions on how to sign up) as soon as that information is available.

What am I doing here?

Albert Einstein will be remembered for many contributions before this one, but this quote has been resonating with me recently:

“If we knew what it was we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?”

Einstein was probably being more self-deprecating than necessary – he knew what he was doing to a greater extent than most scientists of his era, and likely of any era. Perhaps he was just making a joke. Honestly, I haven’t been able to find out much about the origin of this quote – if anyone has more insight, do let me know.

In the absence of additional context, however, I’m going to take Einstein’s words at face value. The obvious interpretation is: we do science because we’re not sure. This is an important thing for science communicators to remember. Scientists may have predictions about how an experiment will turn out, and we think about how various outcomes will support or cast doubt on the hypotheses we’re testing. But we never know for sure what’s going to happen – that’s why we do the experiment!

This uncertainty is part of what makes science exciting, and the thrill of discovery is not an experience that goes unappreciated outside of academia. The best science media give viewers or readers an opportunity to experience that thrill themselves. Robert Krulwich of NPR’s Radio Lab gave the keynote address at last month’s ScienceOnline2011 meeting in Research Triangle Park, NC. On Radio Lab, Krulwich says, he tries to pace the hour-long program so that his audience experiences their own “eureka” moment before he gives them the answer. It’s that moment – and the eager tension listeners feel, waiting to learn whether they’ve arrived at the right conclusion – that Krulwich is after. And he is very skilled at giving his listeners that experience.

I think Einstein’s quote says something else about science, however. It says, more or less implicitly, “we don’t know what we’re doing.” As scary as it is to admit that to a non-scientist – perhaps we fear that our voices will carry diminished authority? – few scientists have trouble commiserating with peers about the uncertainty, false starts, and screw-ups that characterize our day-to-day research.

But should we be afraid to announce to the rest of world that “we’re people, too?” Maybe this fear is misplaced. More scientists are beginning to recognize that they need to take an active role in engaging with non-scientists, and I’d like to propose that these bumps in the road that we experience while doing science might not be just embarrassing faults, best left on the editing-room floor.

Instead, these mistakes are the stuff of stories. No quest is complete without a few wrong turns… and as any TV executive will tell you, audiences love a good quest. Look at Mythbusters, one of the most successful shows on the Discovery Channel. Like it or not, Mythbusters brings more science to more people – including non-traditional science audiences – than just about any other show on television. The producers of Mythbusters never just cut to the chase and tell viewers whether an urban legend is busted or not. Instead, Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman take the viewers on a journey, complete with screw-ups, and the journey itself is the reward.

There’s a fine line to be walked here: on the one hand, we don’t want to give the impression that we’re just bumbling through our work, aimlessly joyriding through what is by many standards a pretty cushy job (doing so, very likely, at the expense of the taxpayers). On the other hand, if we succumb to the prevailing stereotype and portray ourselves as the unfeeling, objective, infallible scientists, we have succeeded only in thoroughly alienating ourselves from the very people with whom we need to engage if we want our work to matter – the public!

Despite the decline of many printed media and the widespread disappearance of regular science columns in newspapers, a legion of online reporters – professional writers and professional scientists alike – are blogging science back to widespread attention. Many of these writers provide timely summaries of important new work, and even better, thoughtful analyses and synthesis of existing research.

But I also think there is a niche that still needs filling, and it’s one that we scientists need to fill ourselves. We need to show people why we do science – it’s not just for the big “aha!” intellectual payoff at the end, or for the fame and fortune (ha ha!) that come with publishing your work in a peer-reviewed journal. We do it because we love the whole process. Science is competitive, and people who don’t love doing it get weeded out pretty quickly.

Because we do it every day, it’s tempting to think that our day-to-day work won’t be interesting to anyone. But let’s turn to another perennially successful show on the Discovery Channel: Dirty Jobs. None of the jobs portrayed on Dirty Jobs is particularly fascinating to the workers who perform that job, day in and day out. But with a fresh perspective (and the wry commentary of Mike Rowe), you have a formula that reliably attracts hundreds of thousands of viewers a week.

We aren’t all going to be great at this kind of public engagement. But I think we should give it a try. Maybe we’ll figure out who among us can be the “Mike Rowe” of science. With any luck, there will be several of Mike Rowes, Adam Savages, and Jamie Hynemans in our midst. Because knowing science is one thing. Knowing scientists is another. And if science is going to matter in people’s lives, I think both are important!

P.S. If you know scientists who are already doing this kind of outreach, I’d love to hear about them!

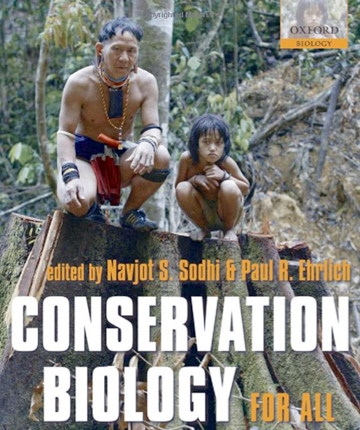

Free Oxford University Press textbook – Conservation Biology For Everyone

Apparently in support of this year being the International Year for Biodiversity, Oxford University Press is making a Conservation Biology textbook freely available. Please pass this email to as many schools, wildlife clubs and others you can and/or print it and give it!!

Apparently in support of this year being the International Year for Biodiversity, Oxford University Press is making a Conservation Biology textbook freely available. Please pass this email to as many schools, wildlife clubs and others you can and/or print it and give it!!

PS-Please post and disseminate to other networks and colleagues!!

Download the 350 pp book free at:

http://www.mongabay.com/conservation-biology-for-all.html

Sodhi, N. S. and P. R. Ehrlich (Eds.) Conservation Biology for All.

Announcing… SustainableFocus.org!

Over the last few months, I have been working alongside a team of scientists and media experts to create a new non-profit organization. We are excited to announce the launch of , an online community and magazine developed to address the growing need for visual communicators, scientists and stakeholders to collaborate on issues of science and sustainability.

The mission of is to foster the use visual media amongst the scientific community. By sharing resources, facilitating discussion, and fostering collaboration, we empower our members and challenge our peers to engage with broader audiences using visual media. When art is used to communicate science, information critical for sustainable decision-making and positive change can reach and motivate broader audiences.

Once you visit the site, however, you’ll also find that many of the resources available at SF are not just about outreach. We have dedicated sections to research applications of digital photography, potential funding sources, and resources to improve peer communication skills – all of which anyone can learn from and/or contribute to.

Among many other attractions, the site has s by a diversity of experts in science, communication and visual media. We have a , , and video galleries, a plethora of web , a marking important dates for conferences, photo/film competition and fund sources, and a diverse of scientists, conservationists and media experts.

We need your contributions to make SustainableFocus.org a thriving community. If you have a moment, please visit the website, create an account, and start sharing and learning ()!

You can also find us on and

Sean Stiegemeler's videos

I saw a few videos by this guys about a year ago. He’s been getting a lot more attention of vimeo recently and has mastered the use of time-laps videos using dSLRs and automized dollies. Once I started looking more into his work, I realized he’s also an awesome photographer. Check out his vimeo videos (my personal favorites are the two posted below) and here is a link to his personal website:

from on .

from on .

Patience makes perfect

I have a confession to make. It’s been a WHILE since I’ve gone out with any serious intention of taking pictures. Until last weekend, in fact, the last time I took nature photos – literally – was a four-day trip through southwestern Australia with Nate Dappen, appended to the end of a professional meeting I attended in Perth. In place of photography, I’ve been working on , video projects, and grants to support my dissertation research.

A Snowy Egret (Egretta thula) in flight with a meal

I finally got the chance to do some photography last weekend at Bolsa Chica Ecological Reserve in Orange County, CA. Birds are the most obvious subjects at Bolsa Chica, and I love taking pictures of birds. And to my genuine (but pleasant) surprise, I still felt comfortable with the controls of my camera. Even better, I was still pretty decent at stalking wild birds and getting close enough for photos.

But something was wrong. I just couldn’t focus – and I don’t mean camera focus, I mean mental focus. It had been so long, I just wanted to shoot EVERYTHING. When a bird wasn’t cooperating, I quickly gave up and looked for a different quarry. I didn’t have the will to stick it out in one spot while nothing good was happening, even though I know that’s how I’ve gotten nearly all of my best images over the years.

I was impatient… If I didn’t capture something great on this trip, I might not have time to shoot again for weeks!

A Savannah Sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis) in wetland vegetation

What I ended up with was a smattering of shots, including, I’ll admit, a few that I’m happy with. But I didn’t feel great about the whole session. At the end of the afternoon’s shoot, I didn’t get that “job-well-done” feeling I sometimes get when I’ve really connected with a subject and captured great images. Instead, I felt flustered, and my mind was scattered. I had to think hard even to remember the first few subjects I’d shot after arriving.

Patience takes practice (and not having photographed for 3 months doesn’t help!), but it’s usually worth the investment. None of the images I captured last weekend feels particularly intimate, which is what I really strive for in my wildlife photos. If I had stuck it out in one spot – if I had been patient – I might have captured something special. But the self-imposed pressure to produce something of quality, the looming prospect of more desk work and less shooting in my future, made that impossible. I lost sight of the long goal – and why I love taking pictures – for the short one.

Next time, I think I’ll just go someplace where the light is nice and sit. I think wildlife photography is a little like Whac-a-Mole. Sure, you can chase every mole, and you’ll probably even hit a bunch, but you might not hit any of them squarely. Wait and watch one hole, though… and that mole is YOURS.

(No moles were harmed in the writing of this post.)